Once the government had decided to establish an internment camp in Colorado many people were against the arrival of the Japanese. It was not long after the establishment of the camp that public opinion turned against the WRA and Amache itself. The Denver Post seemed to always be attacking either the internment camp or the Japanese during the years of the war. The editor of The Denver Post wrote the following on one occasion:

The Post will never agree that while Japanese Barbarians are murdering Americans we should coddle and pet and pamper Japanese enemies here in the United States (quoted in Holsinger 1960: 92).

Other newspapers in Colorado which attacked the Japanese during the war included the Pueblo Chieftain and the Granada Journal.

Not all newspapers were against the internment camp during the war. In one editorial of The Lamar Daily News in 1943 the editor stated:

From a strictly selfish and material standpoint it happens that to date the relocation center is the largest, and in fact the only project this community has received out of the war effort. It has meant the expenditure of thousands of dollars in this region which has meant much to local businesses. Its coming has brought also the hope that this section of the Arkansas Valley would at last receive the long hope for intensive agricultural development which it has so definitely deserved and needed . . . It might be well for the senatorial committee [which has been found by Senator Mon C. Wallgren of Washington] which visits Amache, to say over a few days and look for waste and extravagance and inefficiency in some war projects, about we read no complaint in our indignant Colorado press (quoted in Holsinger 1960: 96-97).

Other newspapers which were favorable toward the evacuees included the Rocky Mountain News and The Monitor.

Despite the newspapers which championed their

cause during the war, public opinion was turned against the evacuees

at Amache. Some of the merchants in Lamar refused to sell merchandise

to the evacuees. Other merchants saved their better merchandise

for their white customers. "No Japs Allowed" signs

were seen in several store windows in Lamar. "Though much

of the animosity against the evacuees was based on the 'terrific

waste of money in building the camp' or on farmers' complaints

that the Japanese now had the best farmland in the state, the

majority of the hostility was based on hatred for Japan"

(Holsinger 1960:

99).

Despite the newspapers which championed their

cause during the war, public opinion was turned against the evacuees

at Amache. Some of the merchants in Lamar refused to sell merchandise

to the evacuees. Other merchants saved their better merchandise

for their white customers. "No Japs Allowed" signs

were seen in several store windows in Lamar. "Though much

of the animosity against the evacuees was based on the 'terrific

waste of money in building the camp' or on farmers' complaints

that the Japanese now had the best farmland in the state, the

majority of the hostility was based on hatred for Japan"

(Holsinger 1960:

99).

Such attitudes led the Colorado Legislature to attempt in 1944 to pass a bill banning Japanese from holding land in Colorado. Rumors spread that former Japanese evacuees were purchasing great quantities of land in Colorado. The Citizen's Emergency Committee, among other organization, came to the aid of the evacuees. Its members included the University of Denver and the University of Colorado. The bill was passed by the House 48 to 15, but it was defeated in the Senate 12 to 15 (Chang 1996: 76).

Not everyone was against the evacuees entering Colorado. The editors of Lamar's newspaper supported the evacuees as well as Bill McGuin, the sheriff of Prowers County, stated the following:

The Japs and WRA employees have been perfect ladies and gentlemen, and Lamar has no cause for complaint. I think if people here knew how these Japs fell about Japan, the trouble and grief the country has cause them - - they would feel different towards the evacuees. Most of them are loyal Americans and they do not want trouble. After all it isn't their fault they're here, and they would be glad to leave and go back home if they could. I think they're doing a grand job out there - - on both sides. If we put that many white people in a relocation camp, under the same conditions there'd be hell to pay. There would be fights everyday and we would feel a lot more resentful than the Japs do (quoted in Holsinger 1960: 99).

The groups who most consistently supported the Japanese were the church groups. The Colorado Council of Church Women of the Rocky Mountain Region, the Denver Council of Churches, and the Colorado Council of Churches all publicly and privately supported the evacuees. The Colorado Council of Churches published The Japanese in Our Midst, which went through several transformations The booklet was published in order to help dispel the propaganda which was circulating about the evacuees. "Off all of the so-called pressure groups in the state during the war, the church-affiliated organizations did the most to advance tolerance and understanding of the Japanese (Holsinger 1960: 103).

The most notable supporter of the evacuees was the governor of Colorado Ralph L. Carr. After the evacuation of the ethnic Japanese from the west coast, Carr welcomed all evacuees to resettle in Colorado. He stated:

This is a difficult time for all Japanese-speaking people. We must work

together for the preservation of our American system and the continuation of our theory of universal brotherhood . . . If we do not extend humanity's kindness and understanding to [the Japanese-Americans], if we deny them the protection of the Bill of Rights, if we say that they must be denied the privilege of living in any of the 48 states without hearing or charge of misconduct, then we are tearing down the whole American system (quoted in Lurie 1990: 58).

The governor's support for the Japanese was extremely controversial. The majority of Western public leaders were anti-Japanese until well after the end of the war. After only serving on term as governor, Carr was overwhelmingly defeated in the U.S. Senate and retired from public life.

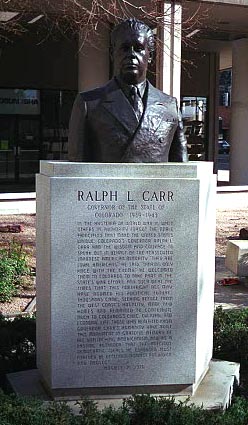

His support of the Japanese has not been forgotten. Just outside of the Colorado governor's office is a plaque dedicated to Ralph L. Carr.

Ralph L. Carr 1887 - 1950

Governor of the State of Colorado 1939 - 1943

Dedicated to Governor Ralph L. Carr:

a wise, humane man, not influenced by the hysteria and bigotry directed against the Japanese-Americans during World War II. By his humanitarian efforts no Colorado resident of Japanese ancestry was deprived of his basic freedoms, and when no others would accept the evacuated West Coast Japanese, except for confinement in internment camps, Governor Carr opened the doors and welcomed them to Colorado. The spirit of his deeds will live in the hearts of all true Americans.Presented: October, 1974 by the Japanese Community and the Oriental Culture Society of Colorado (Lamm and Smith 1984: 137).

In addition to the plaque in

August 1976 a bust of Carr was erected in Denver's Sakura Square.

At the dedication of the bust one speaker described the governor

as one who "rolled up his sleeves on the side of the angels

and helped the Japanese-Americans regain respectability"

(Lamm and Smith

1984: 145). Another person described the governor as "one

voice, a small voice but a strong voice" (Lamm

and Smith 1984: 145).

In addition to the plaque in

August 1976 a bust of Carr was erected in Denver's Sakura Square.

At the dedication of the bust one speaker described the governor

as one who "rolled up his sleeves on the side of the angels

and helped the Japanese-Americans regain respectability"

(Lamm and Smith

1984: 145). Another person described the governor as "one

voice, a small voice but a strong voice" (Lamm

and Smith 1984: 145).