‘A Continuum of Love’: Telling the Story of WWII Japanese-American Internment Camps

University of Denver professor of anthropology Esteban Gomez and recent alumna Whitney Peterson’s new film, “Snapshots of Confinement,” premieres this month on PBS.

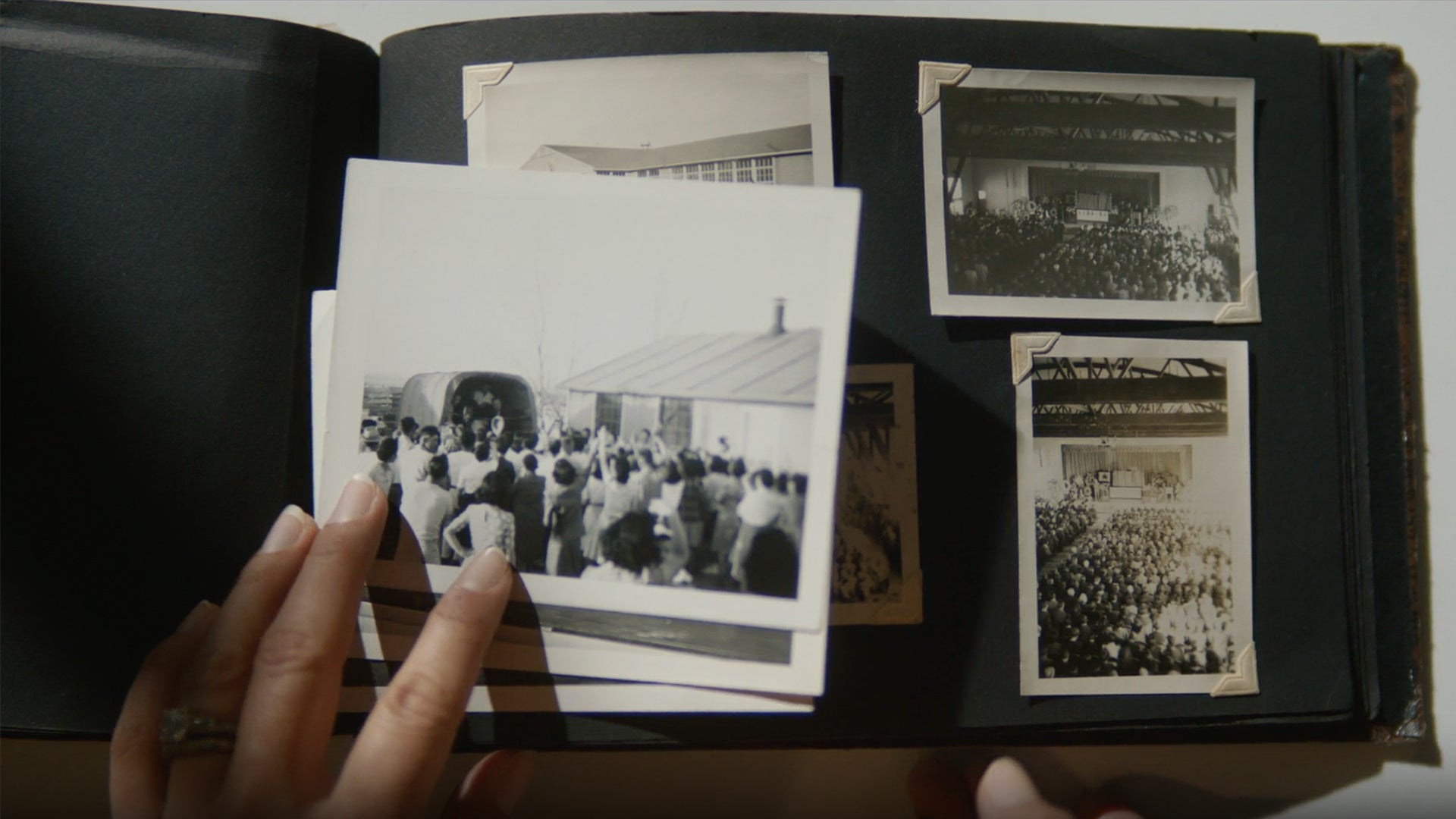

Photo courtesy of Esteban Gomez.

If you search online for the history of World War II Japanese American internment camps in the United States, you’ll find a wealth of photos, some taken by famed photographers like Dorothea Lange and Ansel Adams. But a new documentary film, produced by a University of Denver professor and his former student, digs deeper.

“Snapshots of Confinement,” produced by anthropology professor Esteban Gomez and DU graduate Whitney Peterson (MA ’18), tells the stories of survivors by examining their personal photo albums from time spent in Japanese American internment camps across the country—including Colorado’s Camp Amache, now a national historic site.

The film follows both survivors of the camps and their families and descendants, focusing mainly on the stories of those who were held at Amache.

“There's been a lot of focus on professional and government photography of the time, but really, little attention has been paid to the photographs and albums that the people who were incarcerated were able to take and curate through that experience,” says Peterson.

A journey to filmmaking

Peterson says the project is a long time in the making. More than a decade ago, she worked at Manzanar National Historic Site, a former Japanese American internment camp in Inyo County, California, that is now a museum. There, Peterson participated in the site’s oral history program and worked to curate photographs that people had donated to the museum.

“I had an opportunity to meet so many people who experienced this firsthand—and their family members—and I was just so moved by their stories,” Peterson remembers. “And I was able to continue that work when I came to DU as a grad student.”

Gomez says that Peterson’s work at Manzanar was what really made her grad school application stand out from the rest. When he reviewed her application materials with fellow anthropology professor Bonnie Clark, he says he knew immediately that she was the right fit.

“That’s rare, given the number of applications we review every year, but it just seemed like it made sense,” Gomez says.

And Peterson’s place within the anthropology program at DU did make sense—so much sense, in fact, that her time with Gomez and Clark led to the creation of the film, which is funded by a grant from the National Park Service.

The stories that moved them

One of the interviewees, Rosie Kakuuchi, was incarcerated at Manzanar as a high school student. Her photo album tells the stories of her siblings—a brother who loved to play baseball and a sister who tragically died giving birth to twin girls.

“There are questions about [her death], if that would that have happened if this whole incarceration didn't happen,” Peterson says. “I think it just really shed light on the significant impact that this had on individuals and people's families.”

Another interviewee, Diana Tsuchida, shared photos of her grandfather and father from when they were incarcerated. Tsuchida does her own oral history work about the internment of Japanese Americans during the war.

“I think the photos have been really instrumental in her exploring her own family history and the complex history involved in incarceration,” Peterson says. “I think those photographs are really a touchstone for exploring the complexities of that experience and the identity related to that time.”

Gomez says Tsuchida’s participation in the film was particularly moving.

“The reason why she does this work, this oral history work, is because it's part of this ‘continuum of love,’ this idea that she is renewing this love and attention for this topic, but also reaffirming her identity.”

The film also touches on the singling out of those who came to be known as the “No-No Boys,” boys and men who answered “no” to two questions on a survey given to every Japanese American who was forced into the camps.

The questions were, “Are you willing to serve in the armed forces of the United States on combat duty, wherever ordered?” and “Will you swear unqualified allegiances to the United States of America and faithfully defend the United States from any or all attack by foreign or domestic forces, and forswear any form of allegiance or obedience to the Japanese emperor, or other foreign government, power or organization?”

Those who answered “no” to both questions were prosecuted.

“One of the things that we really focused on during the second half of the film is this question of what it means to be American,” Gomez says. “Diana Tsuchida’s grandfather was one of the No-No Boys. It created a lot of tension between different communities of Japanese Americans [in the camps]. And so, in the film, we explore that tension and how this had a long-standing impact on the Japanese American community long after the war.”

Making history accessible to everyone

Gomez says he hopes the film and its story of discrimination against Japanese Americans will attract young audiences who are interested in the history of social justice.

“I think there are so many different movements across the country right now to limit the number of voices that highlight the critical nature of our history, with more and more conservative school boards, trying to limit what type of history we understand,” he says. “So, I think, in that sense, we wanted to make sure that we created a film that can continue this narrative and make sure that a younger generation can relate to it.”

Hearing from those who experienced discrimination firsthand, Peterson adds, is part of what makes the film so powerful.

“I think we're at this really critical moment where the generations of people who experienced World War II are almost gone; they're reaching 100 years old at this point,” she says. “I think it is this transition—for folks who are now tasked with carrying out carrying on that legacy—I think that's why the photo albums are interesting, because they're this tangible connection to this past, that people physically pass on to younger folks in their family and to new generations.”

Gomez and Peterson say they hope the film inspires viewers to dig into their own family histories—to open the shoeboxes of old photos we all have in our closets or under our beds—because photos can tell a powerful story.

“It's this thing that we often take for granted, these everyday mementos,” Peterson reflects. “I think everyone can relate to having family heirlooms or things in their homes that might tell a story about their own legacy, and maybe their own history as well, and I think these photo albums do tell the story of resilience and community in a way that's really important to reflect on.”

Where to watch

“Snapshots of Confinement” will premiere on PBS SoCal Plus on May 1 at 8 p.m. PST. The film will also be available to stream for free on the PBS website.