DU’s Cookery and Foodways Collection Whets the Appetite for Discovery

This article originally appeared as a feature in the Summer 2021 issue of University of Denver Magazine. Visit the magazine website for bonus content and to read the article in its original format.

In the mood for Italian? Chinese? Something from the grill? Or maybe a salad? What about something battered in Budweiser?

In the basement of DU’s Anderson Academic Commons, Katherine Crowe can fulfill just about any order. The shelves of the Cookery and Foodways Collection are stocked with all the ingredients required to prepare an eclectic full-course educational meal.

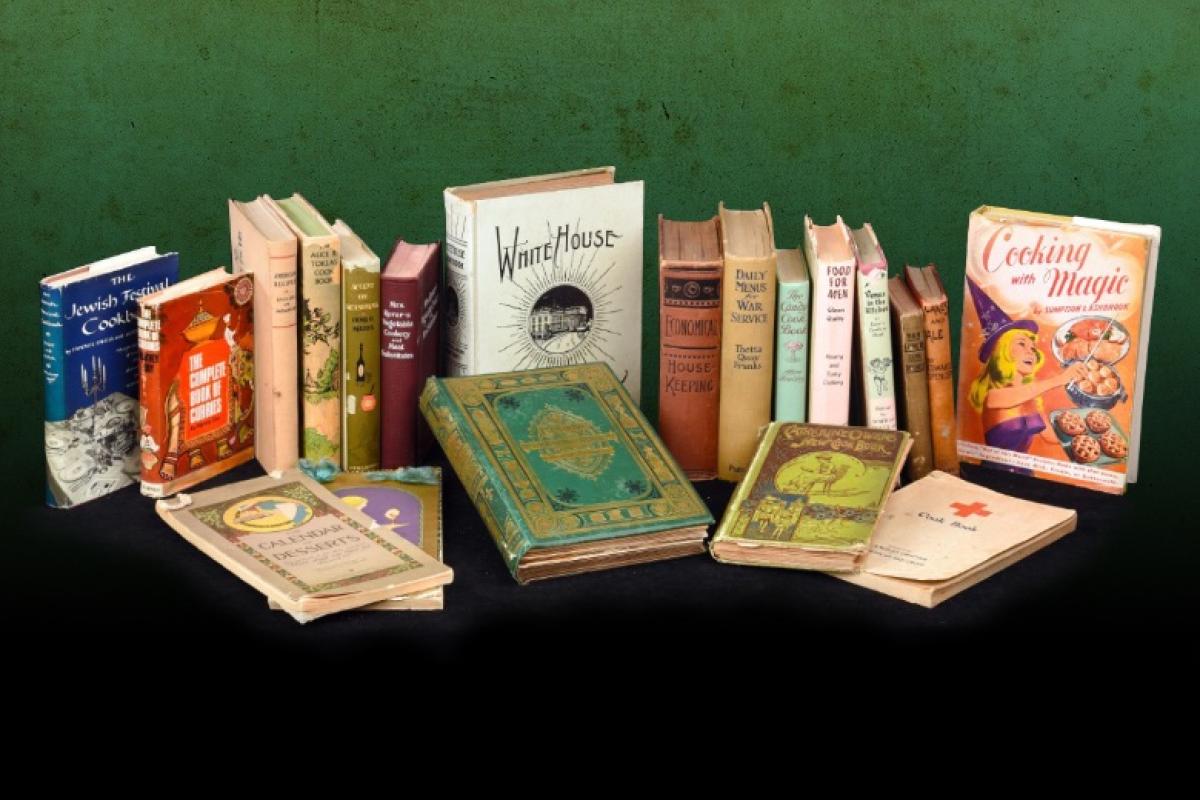

The collection now contains more than 11,000 titles, the bulk of which were donated in 1985 by Margaret Husted, who picked up cookbooks wherever she could find them, be it on a vacation abroad or in her local community.

“She was really trying to collect with both depth and breadth,” says Crowe, curator of Special Collections and Archives. “She ended up with some really rare cookbooks. We’ve had researchers reach out to us because we’re one of two or maybe three institutions that have them. She really did try to collect a wide variety of popular and less available [books].”

Generally speaking, the Husted Collection sticks to American-published cookbooks from the 19th and 20th centuries, but the variation within that genre feels limitless. Cuisine could be classified geographically, ethnically or religiously. Some works are cultural (“A Skier’s Cookbook”) while others are corporate (“Pillsbury Party Time Recipes”). Some originate with national organizations like the American Red Cross, while others come from the community, such as a title from the Ladies Auxiliary of Arvada, created to raise funds for a church.

“It’s not just large publishing houses and what they put out,” Crowe says. “[Husted] really did make an effort to collect things that were special—small community stuff or random ephemeral commercial stuff—which is hard to find because people usually just toss it.”

The Cookery and Foodways Collection also features cookbooks and archival papers from local food luminaries Helen Dollaghan, who served as the Denver Post’s food editor from 1958-1993, and Katie Stapleton, a philanthropist and radio cooking show host. Betty Carey, a former University Libraries Association president and gourmet cook, donated the books she amassed in her lifetime. Walter Scheib III, who served as executive chef to Presidents Bill Clinton and George W. Bush, bequeathed some of his papers as well, including menus from past state dinners.

A tantalizing spread for scholars

Both scholars and students have feasted on the archival riches, and not just for culinary inspiration. Author Adrian Miller drew upon some of the material for his James Beard Award-winning book on the history of soul food and another volume on African Americans who have fed first families in the White House. Miller’s mention of DU’s collection to the Scheib family inspired their donation.

Students in Carol Helstosky’s history classes have consulted the recipes as they study everything from gender roles to the economy to social norms.

“There’s all kinds of cultural aspects you can read into when you look at cookbooks,” says Helstosky, an associate professor. “It offers suggestions or an idea of how you might want to prepare food or live your life.”

In “Cooking for the Liberated Man,” for example, students can examine what society deemed acceptable for men to cook, in contrast to a book aimed at women who are becoming brides.

Politics and food intersect too, especially during times of conflict. During World War I, American recipes focused on thriftiness to accommodate shortages and rations. Years later, when Prime Minister Benito Mussolini mandated his citizens buy only Italian goods, cookbooks compensated. How, for example, can one make coffee without using coffee? What about cake without flour?

Other students have focused their research on the history of vegetarianism, the commercialization of breast milk, the popularization of body building and the prevalence of food allergies, to name a few.

In one way or another, Crowe says, just about every cookbook functions as a historical record.

Nearly everything in the collection must be accessed in-person—not via the internet. That, Helstosky says, has made traditional academic research a hands-on experience.

“It just naturally is exciting to deal with, analyze, grapple with primary sources,” she says. “Sometimes in the cookbooks you’ll see food stains on the pages or something. Or you might see margin notes or a newspaper clipping on pages. It’s that sense of really coming to terms with: ‘Wow, this belonged to someone and someone used it, and it had a real material or pragmatic practical purpose in someone’s life.’ That is always super exciting for students.”

Often, Crowe has found, that excitement in the process leads to better, more satiating research.

“They can really dig in and ask original questions that they developed based on actually spending time with the resources itself, rather than questions that are handed to them,” she says. “I really try to encourage openness and curiosity, because you really don’t know what you’re going to find.”