Sharing the Legacy of DU Student Jack Nathan at a New York City Gallery

In the middle of New York City’s bustling streets, right by the Brooklyn Bridge, you’ll find a new, colorful, pop-up art gallery. It shares a story best told through the work hanging on the walls. A story of ambition. A story of grief. And a story of perseverance.

The Happy Jack Gallery celebrates the life of the late Jack Nathan, a University of Denver student who died in the summer of 2020. The walls are covered with Jack’s creations and with the work of a close friend, DU student Eli Bucksbaum. The gallery raises awareness for mental health — a mission Jack, who contended with anxiety and depression, supported through the launch of his clothing company Happy Jack.

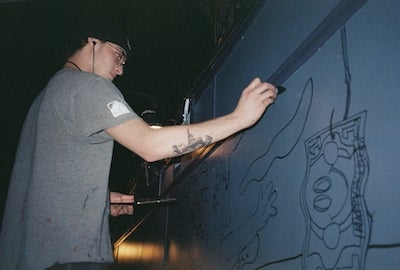

The passion in the paintings testifies to a friendship started at DU and their times as roommates.

“One day we just decided to go to Michael’s and get a bunch of paint and canvases and go downstairs and just paint because there was nothing else to do,” Bucksbaum says. “Both of us just fell completely in love with the idea of art. It was really fun. We would just paint. It’s as simple as that.”

And as simple as that, they bonded through their art. It was an outlet that Jack always made time for because, as he would tell Bucksbaum, you get to decide how your day goes. “If your anxiety pops up, try and fill it with something that you know is going to relieve it. He found his own coping method, and that’s the biggest battle of anxiety is finding ways to deal with it. You’re not getting rid of it, but maybe you’re putting it into something and you’re creating something bigger — that’s what Jack did.”

Jack was not one to wait for life to happen to him. “He was a go-getter,” Bucksbaum recalls. So when the two friends took an entrepreneurship class taught by Daniels College of Business professor Stephen Haag, the wheels started turning for Jack.

Their assignment was to come up with a business idea and make a dollar off of it, and that was when the idea for Happy Jack clothing was born. Jack started buying clothes and using the on-campus heat press to imprint his designs. When the ink ran out one day, Jack bought his own press and installed it in his room.

“I remember I walked into his room after class, and he [had] 20 hoodies with printed designs on them,” Bucksbaum says. “We just started going to thrift stores, and he would buy as many clothes as he could and then print his own designs on them. After about a week, there was like 150 articles of clothing in his room.”

Happy Jack’s motto reflects its namesake’s personal philosophy: “To the individuals who struggle with life, who thrive in life, and who simply, live life. I look forward to making this world a better place with you all.” Jack wanted not only to spread awareness, but also to support organizations doing the same.

“He always had the charitable mindset with everything,” Bucksbaum says. He remembers when Jack first made a profit. He couldn’t wait to write a check to support Child Mind Institute and Active Minds, organizations that raise awareness about mental health challenges facing children and young adults.

Although Jack wasn’t able to launch many of his designs, his legacy carries on. His iPad contained hundreds of designs, and his mother, Bradi Harrison, now puts those on shirts and keeps his business running with Jack's father, David, and his sister, Drew. Jack’s designs are spotted on shirts and hoodies all over the country. They also are for sale at the new pop-up shop.

The shop continues Jack’s mission to destigmatize mental illness. Harrison asked Bucksbaum to curate the gallery, and he also is displaying some of his own artwork, which is available at the silent auction where 50% of the profits will be donated to Child Mind Institute in honor of Jack.

“Now with the gallery, it’s really a tribute to honor Jack,” Bucksbaum says. “I tried to show the art in the way that [he] and I wanted to show our art, because we always talked about having a gallery. I miss him, and I feel like this has brought me closer to him, and it’s helped me cope. I just feel like it’s my duty as his friend to do the things we talked about.”

Painting has helped Bucksbaum deal with the complicated feelings of grief. His work relies heavily on wisdom from Jack. For example, his preference for thick layers of paint speaks to his understanding of the human psyche. “Those are all the anxieties — the things we deal with that are dark and miserable and make us sad, but they are not what define us,” he says. “They just have the most layers. They’re just the things that really build us as humans, but it’s not our overall representation of us. It’s just what’s underneath.”

When people step into the gallery or look at the artwork online, Bucksbaum wants them to understand Jack — a go-getter, someone who didn’t care about the constraints of society, someone who was making a difference with his art. Bucksbaum says the message Jack would want people to take away from the gallery is simple: “It’s the cheesiest thing, and everyone hears it, but just be you. Be yourself. And people say that a lot, but he meant it, and he did it.”