Q&A: Revisiting the Influenza Pandemic of 1918

A University of Denver historian examines the outbreak’s origins and consequences

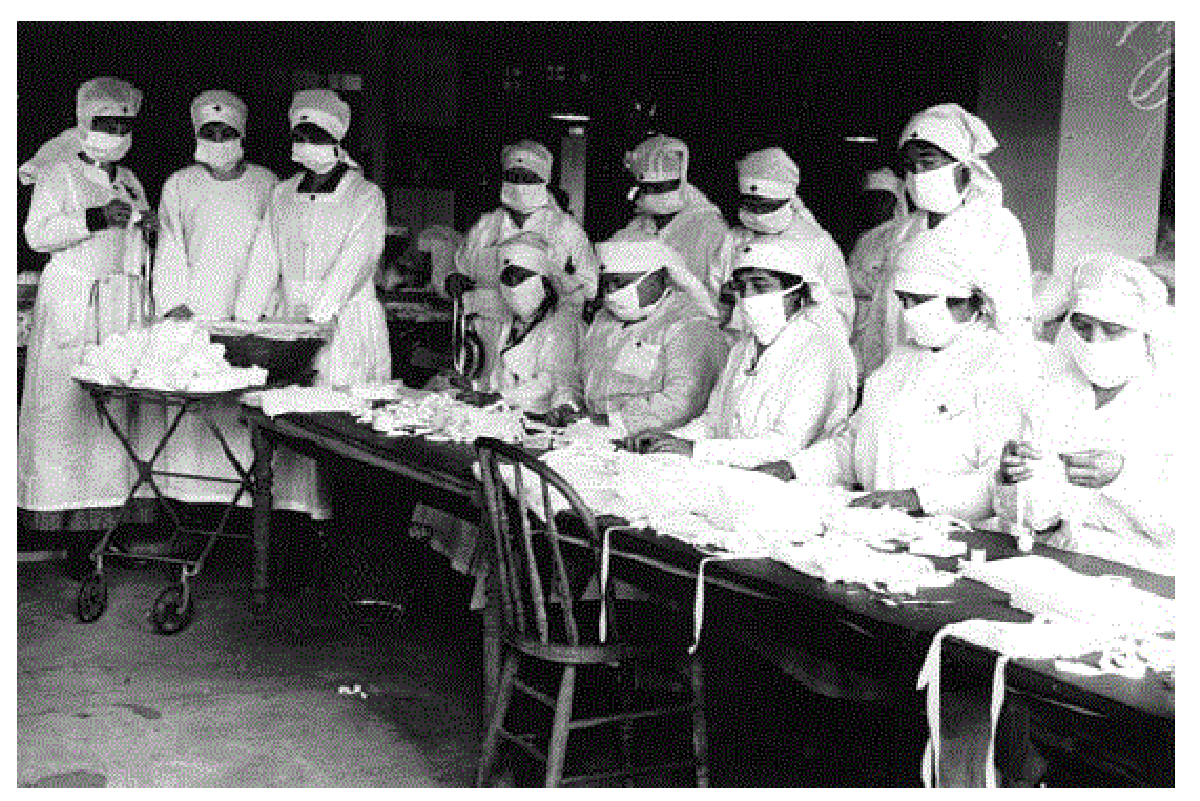

With protective equipment in short supply, Red Cross volunteers in Massachusetts gather to assemble gauze influenza masks destined for Camp Devens outside of Boston.

From the Black Death in the 14th century to today’s COVID-19 outbreak, pandemics have disrupted everyday existence, upended economic life and killed indiscriminately. One of the most lethal pandemics occurred just over a century ago, when a particularly virulent form of influenza spread from continent to continent, claiming thousands of lives in Colorado along the way. Susan Schulten, a professor in the University of Denver’s history department and author of “A History of America in 100 Maps,” gives us the inside story on the deadly influenza epidemic of 1918.

The outbreak of what came to be called the Spanish flu ranks among the most deadly pandemics in modern history. How bad was it?

That is a tricky question. We don’t have a reliable figure for how many died from the influenza pandemic of 1918. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that 500 million people worldwide were infected, while between 50 and 100 million succumbed to the disease — the equivalent of 200 million today. Historian John Barry estimates that the pandemic’s toll exceeded military casualties from the First and Second World Wars. Within the United States — in the space of just 15 months — the pandemic killed 670,000 Americans.

To put that in perspective, you were far more likely to die from the flu than from combat in World War I. Here in Colorado, about 1,000 died in the First World War; many of them were killed by the flu. Compare that to the more than 7,500 Coloradans who died from the flu from September 1918 to the early months of 1919.

Even the name is somewhat mysterious: It became known as the Spanish flu, not because it originated there, but because Spain was one of the few nations that did not censor news during the war. Because the Spanish press covered the epidemic early on, it quickly became named the “Spanish flu.”

Where did the disease start, and how did it spread?

The most common explanation is that the disease originated in Haskell County, Kansas, which sits on the pathway of several bird migration flyways. Birds may have brought the infection to hog farms in that area, where it mutated into a virus that could infect humans. What resulted was a new and more lethal strain of influenza.

However it originated, it spread quickly in January 1918. Those infected sought treatment at Camp Funston, a U.S. Army training camp at Fort Riley, near Manhattan, Kansas. In doing so, they spread the disease to the many men training for combat in Europe. That early outbreak infected thousands and killed dozens. Those who survived or were asymptomatic carried the disease to other military camps across the United States, and from there into civilian life through the nation’s towns and cities.

The war itself tremendously accelerated the spread of the disease: All across America young men mobilized into cantonment camps, where the disease quickly proliferated. From there, American soldiers brought the disease to the front lines in France, where the conditions were ripe for further transmission. In fact, it was through soldiers that the disease returned for a second wave in the autumn of 1918. After a slight reprieve over the summer, the disease was brought back to the United States through soldiers at Camp Devens near Boston. This second, far more lethal wave of influenza overwhelmed the military hospitals.

Who was most likely to die from the Spanish flu?

This remains one of the most remarkable aspects of the pandemic: It was particularly deadly for the young, while older Americans fared better, perhaps because they had lived through prior flu epidemics and gained some kind of immunity. By contrast, it was those in their 20s and 30s who were especially vulnerable to the 1918 pandemic. They got sick, and they recovered in much lower rates than others. The virulence of the disease was particularly shocking — sometimes a victim would succumb within 12 hours of showing first symptoms, having suffered from fluid in the lungs or from an inability to form blood clots. People died faster than they could even be buried. Philadelphia was hit especially hard, though the disease reached far and wide across the country. But others survived.

Denver’s experience with the flu was pretty horrifying. By the end of 1918, the city had logged 12,718 influenza cases and 1,218 resulting deaths — a rate reportedly much higher than other cities of comparable size. What made Denver so susceptible to an exacerbated outbreak?

Here in Denver, the first influenza-related death was actually a DU student, Blanche Kennedy. On Sept. 27, she died near campus after returning from a trip to Chicago. The University closed soon thereafter, while several other institutions such as the Jewish Consumptive Relief Society (JCRS) instituted a severe quarantine to protect their patients, who were recovering from tuberculosis. As a result, the JCRS did not lose a single patient to influenza.

It was not until early October that local officials recognized the pattern of infection. On Oct. 6, an order was issued that closed all schools, churches, clubs, movie houses, theaters and other indoor congregation spots. As Denverites continued to congregate outdoors and the infection rate increased, orders were issued to cease all gatherings. Local cities and municipalities also began to quarantine residents, while also limiting the number of passengers on tramway cars, staggering business hours to limit congestion, and issuing prohibitions on other behavior such as spitting.

By late October, the public grew restless with the quarantine orders. The mayor began to discuss the possibility of relaxing restrictions by reopening theaters and schools. Yet despite the improved numbers, poor and immigrant neighborhoods of Denver continued to suffer. The city imposed strict quarantines in Globeville and Little Italy, while other areas of the city began to reopen for business. But this was premature. In fact, on Nov. 11, the official end of the war, thousands attended a celebration downtown. Unsurprisingly, Denver experienced a new surge of the infection. Restrictions returned, this time with more enforcement powers and stricter measures, such as mandatory face masks for all in public. But none of these policies matched those of Gunnison, which prohibited any visitors. While 8,000 Coloradans died from the flu that year, only one passed away in Gunnison.

How did the American public respond to the flu’s rapid spread?

It’s important to understand that the flu hit the United States at the peak of wartime mobilization, when Congress had passed draconian controls on dissent and anti-war sentiment. We can only imagine this climate of fear, compounded by the arrival of a lethal epidemic. This wartime circumstance, to some extent, complicated efforts to inform the public and to reveal the true extent of the disease. In fact, the deadliest wave of the flu in fall 1918 coincided with rumors of imminent end to the war with Germany. In other words, we cannot separate the war from the pandemic. In Philadelphia, for instance, plans went forward for a September parade to promote Liberty Loans. Instead of canceling the parade to protect public health, the threat was downplayed by leaders and news editors. The parade went on as planned, with disastrous consequences for the city. Within six weeks, Philadelphia lost 12,000 to the flu. This created tremendous distrust and fear.

What finally put a stop to the pandemic?

I’d like to say it was modern medicine or the discovery of a vaccine. But the virus burned itself out, as do most seasonal viruses. There was a third and final wave in January 1919, which even infected President Woodrow Wilson while he was attending the peace negotiations at Versailles.

On a side note, last year I came across a letter in the Truman Presidential Library from Harry Truman —then stationed in France near Verdun — to his fiancée Bess Wallace. Captain Truman wrote lovingly to Bess as she recovered from influenza back home in Independence, Missouri.

With the coronavirus raging around us, are you expecting new interest in the pandemic from your history students?

As it happens, this year I supervised a senior thesis by history major Brian Brunst on the flu pandemic here in Denver. Brian was especially interested in the way that Americans have relegated the flu to a footnote in history, even as it took far more lives than the First World War. He noted that news about the war dominated the newspapers, displacing coverage of the flu. Even after the end of the war in November, when the flu was ravaging Denver, news coverage prioritized the situation in Europe. How strange, then, that the more immediate threat to the local population received less coverage than comparatively distant events across the Atlantic.

This tendency to downplay the severity of the epidemic was not limited to news outlets. As historian Carol Byerly has observed, medical officers within the military also contributed to the lack of understanding and attention by writing the epidemic off as an exceptional event. In fact, it was not until the 1970s that historians began to pay close attention to the epidemic. Since then, several scholars have restored this event to its rightful place in history, exploring the multiple ways that it affected the home front and the battle front, war and peace, towns and cities, military and civilian life. When I began to supervise Brian’s research, I thought of it as a historian, ordering facts to make sense of causation. I now think of it as living history, much more immediate to our current moment.