Alison Schofield Tackles New Translation of the Dead Sea Scrolls

DU professor is one of three editors on an international project

Alison Schofield is truly living her childhood dream. An associate professor of religious and Judaic studies, she works with some of the most intriguing ancient manuscripts in Judaism and Christianity.

“I was always a fan of Indiana Jones, and I was always interested in the Middle East,” Schofield says. “I’ve been interested in the Dead Sea Scrolls for as long as I can remember.”

That interest has paid off. Today, she is part of a three-editor team working to create a new translation of the famous scrolls. “My field tends to be male-dominated,” Schofield says. “For the first time in history a woman has been selected to one of the highest roles of editing, and also being an American, because generally it has been European scholars.”

Her interest in the scrolls started when she was growing up. While in high school, she attended her first conference on the texts. And when she pursued her college education, she focused on the Middle East, the Hebrew Bible, archaeology, and of course, the Dead Sea Scrolls.

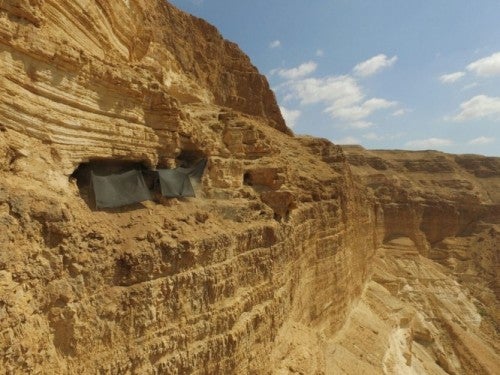

The discovery of the scrolls is considered one of the most significant archaeological finds of the 20th century. The Dead Sea Scrolls contain some of the oldest copies of the Bible and Jewish literature dating to the time of the Second Temple in Jerusalem. They were first discovered in mountain caves east of Jerusalem in 1947. However, discoveries continue to be made even today as archaeologists search 12 different caves overlooking the Dead Sea. Many of the scrolls are on display today at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem.

Schofield has been traveling to Israel for more than 20 years, and for the last 10 years she has worked directly with the manuscripts. As the technology to sense and decipher the scrolls improves, new fragments are unearthed throughout the caves. Two years ago, Schofield was named to the editorial team tasked with producing new critical editions of the prized works. These will feature translations of newly discovered fragments and improved reconstructions of previously published texts.